Amicus curiae briefs abound in the U.S. Supreme Court. The rules on filing are sufficiently loose that almost anyone with the necessary funds and that is able to follow the proper filing procedures can file an amicus brief. According to Justice Ginsburg these briefs along with other secondary sources can aid the Court in its decision-making: “There is useful knowledge out there in friend of the court briefs, law review articles we can read, in the decisions made by tribunals elsewhere in a world community grappling with the same difficult questions.”

Contrastingly, due to the number of amicus briefs submitted to the Court the Justices candidly share that they cannot and do not read through all of them. In the 2015 calendar year by itself groups filed over 1,400 amicus briefs with the Court. The Justices have various resources to sort through this glut of briefs to focus on those with a high likelihood of relevance. In Pepper’s and Ward’s In Chambers (2012), Justice Ginsburg (p. 395) shares that she puts the thrust of this sorting task on her clerks’ shoulders – “Their [clerks bench memos] job is to give me a road map through the case, and then I can read the briefs. They also tell me which of the green briefs (Amicus) I can skip.”

This post looks at some of the defining aspects of the most effective amici before the Court both this Term and throughout the years of the Roberts Court. To narrow the list of potential amici of focus, I examined the number of amicus briefs filed by various interest groups for the 2015/2016 Supreme Court Term (the source for this search was SCOTUSBlog’s lists of briefs filed in the individual cases and so the search criterion was the group on the brief’s title). I chose a cut point of 4 amicus briefs submitted on the merits for the initial set of filer groups. The table below shows the number of merits case amicus filings for each of these groups during the 2015 Supreme Court Term.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed the most with 11 followed by the Chamber of Commerce of the United States with 10, and AARP and The Cato Institute with 8. These figures provide a sense of these groups engagement with cases across the Term. They also provide one way to look at the most powerful interest groups before the Court in the sense that they have the resources and access to file repeated briefs throughout the Term.

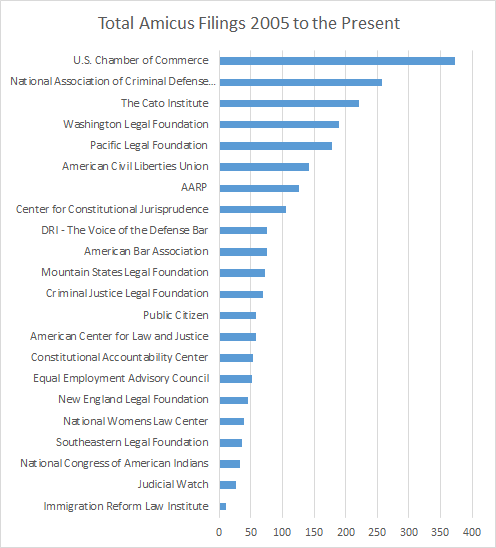

Many of these groups have consistently filed a large number of briefs each Term since the beginning of the Roberts Court (beginning with the start of the 2005 calendar year). The Table below provides their overall amicus filing figures.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce filed far and away the most amicus briefs with 373 followed by the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) with 258. Rounding out the top five are the Cato Institute with 221, the Washington Legal Foundation with 190, and the Pacific Legal Foundation with 178.

How consistent have these groups been across the years? The following chart provides a graph of the top ten total amicus filers for the 2005-2016 (until present) in terms of per year total amicus filings (to generate these numbers I searched for these groups’ names in the “Title” field of LexisNexis Supreme Court Briefs searches for the respective years).

Some groups like the Chamber of Commerce of the United States filed a high number of amicus briefs across these years while others like the Cato Institute filed considerably fewer briefs at the beginning of this period and increased their filings over the course of these years. Three groups covered in this graph that were not previously mentioned are the Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence, DRI – The Voice of the Defense Bar, and the American Bar Association (ABA).

The question still remains of how effective these amici are at conveying their messages to the Supreme Court. Without greater insight into the psyches of the clerks and Justices we must use proxy measures to gauge this efficacy. One measure I used in an earlier post was looking at overall citations to the entities in question in Supreme Court opinions (in majority and separate opinions and footnotes by searching for each group’s name in the text of the opinions).

Topping this list is the NACDL with 21 followed by the ACLU with 11 and the Chamber of Commerce of the United States with 8. Other groups with a high number of mentions include the ABA and the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation with 5 each, Public Citizen, Inc. with 4, and the American Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ) with 3.

Using these numbers combined with the total number of amicus filings*, I created an Amicus Effectiveness Score that is simply the number of cases where a group’s amicus briefs are cited divided by the total number of amicus filings for the group. The groups are ranked below according to this metric (groups with zero citations are excluded).

Not only was the NACDL cited the most across the entire period, but it was also the most effective amicus according to this metric. This group is followed by the ACLU, the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, Public Citizen, Inc., and the ABA. The Chamber of Commerce of the United States which filed the most amicus briefs over this period placed in the lower half of the groups for overall effectiveness. This strengthens the claim that the number of filings on the aggregate does not necessarily lead to more citations. On the other hand, it does not show that these briefs are not read by the clerks and Justices, and other measures can be (and have been) developed to convey the influence these groups have on Supreme Court jurisprudence (such as associations with case outcomes).

Equally important is the fact that some interest groups are more general in nature and in their attempts at providing the Court with information, while others focus on specific cases. Even groups that target specific cases, however, are effective under this measure as is indicated by the presence of groups like the National Congress of American Indians.

* Results are substantially similar including and excluding cert level amicus filings. To locate cert stage briefs I searched both for language in the brief’s title and in the brief’s conclusion section that specified that the brief was focused on the cert stage.

[As a disclaimer, the search methods I used in this post may not have captured the entire universe of amicus briefs of interest but due to different spellings of groups names and inclusions and exclusions of groups names on the titles of briefs it is nearly impossible to ensure the capture of all such briefs without combing through each brief and opinion by hand and without the benefit of specific search terms.]

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

Update 1/5/2017: Public Knowledge should be included in the groups that filed four or more merits briefs in the 2015 Supreme Court Term.

This is an interesting analysis, thanks! The problem, in my view, is that there are numerous confounding variables that make it difficult to assess amici’s effectiveness once the case has been granted plenary review. Like you mentioned, these amici may be more “effective” simply because they are providing additional factual materials on a side that they identified is likely to win. I think a more revealing inquiry into amici “effectiveness” might be at the cert-stage, where I would expect that the presence (or absence) of certain amicus briefs may make a grant more likely.

LikeLike

I agree that this is one and definitely not the only way to look at amicus effectiveness. It is a way that has not been thoroughly explored before and due to the lack of availability of inter/intra-chamber memos it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of amicus briefs on the merits in other semi-objective manners. Also if you’re interested in amicus stage cert I discuss it in my paper “Finding Certainty in Cert” (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2715631).

LikeLike